Revisiting 1868 to Inform Disaster Preparedness - 4/6: Kīlauea’s Forgotten M7 Quake

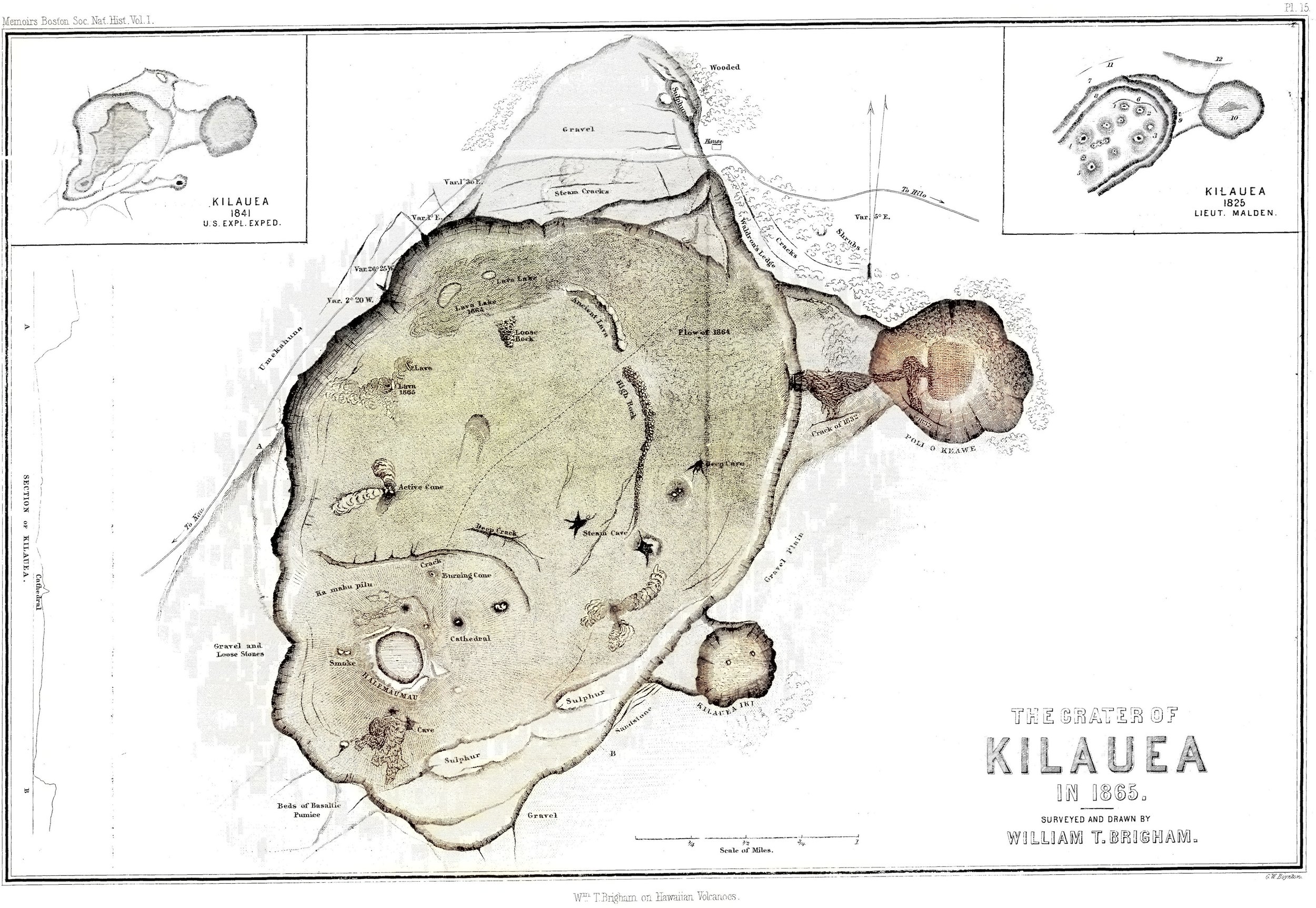

Map and cross section showing the collapsed area within Kīlauea caldera following the events of 1868. Colorized with Capcut AI and enhanced with 1865 map (see below) from Brigham, W. T. (1909). The volcanoes of Kilauea and Mauna Loa: B. P. Bishop Mus. Mem., vol. 2, no. 4, 222 pp., Honolulu.

The series of disasters on Hawaiʻi Island between March 27 and April 11, 1868 includes the largest earthquake ever reported in Hawaiʻi, estimated at magnitude 7.9, to go along with two other magnitude 7’s and countless smaller events, devastating landslides and tsunamis, four eruptions in total at both Maunaloa and Kīlauea volcanoes’ summits and southwest rifts, and finally significant collapses atop each volcano. If such a sequence were to repeat today, residents’ knowledge and preparedness could go a long way in mitigating its impact, especially in minimizing the damage to human lives and well-being. In that spirit, we present a series of 6 short articles that recap each phase of the sequence and its relevance to those of us on-island.

Map of Kīlauea caldera in 1865, prior to the 1868 collapse, colorized with Capcut AI from historic paper map entitled: Wm. T. Brigham on Hawaiian volcanoes (1868), G.W. Boynton, sc. Pl. 15 : Crater of Kilauea in 1865, surveyed and drawn by William T. Brigham. Memoirs Boston Society of Natural History, vol.1.

Today, we examine the fourth phase of the sequence, an often forgotten magnitude 7 earthquake on Kīlauea, and its possible consequences including a small Kīlauea Southwest Rift eruption and collapse at Kīlauea summit. During the first phase, Maunaloa erupted briefly at its summit, intruded its Southwest Rift, and triggered a magnitude 7.1 quake on March 28. In the second phase, a magnitude 7.9 quake on April 2 caused widespread damage, collapses, landslides, a freak mudflow and a tsunami, through which altogether perhaps 100 people perished. In the third phase, the Great Quake triggered the draining of lava from Kīlaueaʻs summit and its intrusion into the rift zone(s) accompanied by many earthquakes, along with a brief eruption within Kīlauea Iki.

Following the April 2 earthquake, the Pacific Commercial Advertiser reports “another of nearly equal force at 12:30 on the morning of the 4th”. This is corroborated by USGS Professional Paper 1806 which provides that “the 1868 earthquake aftershock sequence included a second earthquake of high magnitude (~M7) beneath Kīlauea’s south flank, resulting in the generation of a second tsunami.” This becomes the third earthquake greater than magnitude 7 within the 16-day sequence.

Clip of the Pacific Commercial Advertiser from April 11, 1868, which reports the existence of a third earthquake larger than magnitude 7 during the 16-day sequence of events.

How could a magnitude 7 earthquake be “forgotten”? Perhaps it was because it released much less energy than locals had just experienced in the magnitude 7.9 two days earlier. Newspapers of the era were only published weekly with information often exchanged by written letters, so maybe reports of the two earthquakes were confused. When damage was assessed after April 4, it may not have been possible to separate the effects of the 7.9 from the 7.0 in areas without eyewitness accounts. USGS PP 1806 notes “it appears that Kīlauea had more damage than one would expect” before accounting for the additional earthquake. In any case, much of the scientific literature does not mention this third big quake.

Map of Kīlauea’s 1868 eruptions drawn in yellow, at the summit within Kīlauea Iki at the top right, and 9 miles down Kīlauea’s Southwest Rift at the bottom left. USGS data plotted on Google Earth.

As a result, there is ambiguity in the timing of Kīlauea’s events, but one believable scenario is that Kīlauea Iki erupted on April 2 as a result of the impact of the 7.9, and that perhaps the initial draining into the Southwest Rift began shortly thereafter. Magma pressurizing Kīlauea’s Southwest Rift may have triggered the April 4 earthquake, further opening the rift and causing significant collapse at the summit, while feeding a small and brief eruption 9 miles away. It’s also possible that Kīlauea Iki erupted on April 4, in conjunction with the magnitude 7 event. Could the 7.9 still be solely responsible for all these effects? Perhaps, although as explained by a 1994 USGS Volcano Watch article, “extension across Kīlauea’s southwest rift zone would not be expected [from the interpreted slip area during the magnitude 7.9 earthquake]… because the southwest rift zone was not a boundary of the proposed active block”. Thus this third large earthquake would have been the perfect candidate to cause that opening and extension.

Close-up map of Kīlauea’s 1868 Southwest Rift eruption, with new lava outlined in yellow. Such a small footprint suggests the eruption was only briefly active, perhaps for only a few hours. USGS data plotted on Google Earth.

It does seem that from April 2, Kīlauea’s lava lakes began to shrink and drain as a result of the 7.9, and that by April 5 there was no lava visible on the volcano. The April 4 quake may have accelerated the process and enabled a bigger summit collapse, which occurred to a depth of 300 feet with a volume nearly one-fourth of the collapse in 2018. As that recent experience taught us, many earthquakes would accompany such a collapse, and shaking was widely felt as far as Hilo until April 9, when finally people there reported getting a restful night’s sleep as the collapse had presumably ended.

As challenging as 2018 was for residents to experience, we can only imagine how much more demanding the combined events of 1868 would be. Beyond Kīlauea, the intrusion in Maunaloa’s Southwest Rift which began the cascade of phases had still been migrating south, and was due to erupt massively in Kahuku on April 7. That will be the topic of our next article in this series, as we consider the challenge of one of our worst-case series of disasters and use that to improve our preparedness today.

#Maunaloa #Geology #Hawaii #1868Eruption #HawaiiHistory