Revisiting 1868 to Inform Disaster Preparedness - Full Version

The series of disasters on Hawaiʻi Island between March 27 and April 11, 1868 includes the largest earthquake ever reported in Hawaiʻi, estimated at magnitude 7.9, to go along with two other magnitude 7’s and countless smaller events, devastating landslides and tsunamis, four eruptions in total at both Maunaloa and Kīlauea volcanoes’ summits and southwest rifts, and finally significant collapses atop each volcano. If such a sequence were to repeat today, residents’ knowledge and preparedness could go a long way in mitigating its impact, especially in minimizing the damage to human lives and well-being. In that spirit, we briefly recap each phase of the sequence, then go through in detail and share its relevance to those of us on-island.

During the first phase, Maunaloa erupted briefly at its summit, intruded its Southwest Rift, and triggered a magnitude 7.1 quake on March 28. In the second phase, a magnitude 7.9 quake on April 2 caused widespread damage, collapses, landslides, a freak mudflow and a tsunami, through which altogether perhaps 100 people perished. In the third phase, the Great Quake triggered the draining of lava from Kīlaueaʻs summit and intrusion into the rift zone(s) accompanied by many earthquakes, along with a brief eruption within Kīlauea Iki. In the fourth phase, another magnitude 7 quake rocked Kīlauea, opening its Southwest Rift to feed a small eruption and cause collapse at Kīlauea summit. In the fifth and final phase of the sequence, Maunaloa erupted on its Lower Southwest Rift as its own summit collapsed.

Maunaloa’s April 1896 summit eruption as painted by Hitchcock, perhaps similar to the events at the start of the sequence of March 1868. Image from USGS Open-File Report 2018-1027.

It all began then with a brief Maunaloa summit eruption on March 27, whose glow was visible beneath a massive column of fume at dawn from the whaleships in Kawaihae harbor on the northwest part of the island, as well as Maui and Molokaʻi. Those days lacked monitoring instruments deployed across the mountain, such that today we would likely have months of building earthquakes and ground deformation, similar to what we experienced in the build-up to its eruption in 2022. Back then, they knew the eruption was brief as there was no glow from Maunaloa’s summit that evening once dark fell.

Maunaloa’s May 1916 eruption as seen from Kīlauea, with fumes rising from Maunaloa’s Southwest Rift at the 11,000 foot elevation. The initial stages of the 1868 sequence may have looked similar, as magma began to intrude the Southwest Rift after a brief summit eruption. Photo by H. Wood and courtesy of the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa Hamilton Library, via May 19, 2020 USGS-HVO Volcano Watch, and restored with Capcut AI.

Often on Maunaloa, a short summit eruption can lead to an intrusion of magma into one of its rift zones. In 2022, that was the Northeast Rift whose eruption only threatened the weather observatory and the Saddle Road. In 1868, an intrusion followed into the more populated Southwest Rift over the next several days, initiating a dramatic 2-week cascade of events.

On March 28, large earthquakes began to be reported, with the first major shock estimated at magnitude 7.1 around 2pm centered under Kaʻū, followed by 9 sizable aftershocks within the next 24 hours all felt in Hilo. Most likely, as magma intruded into the rift, it shoved Maunaloa’s southeast flank which then moved in response, allowing the magma to intrude and push further, leading to more earthquakes. The initial shaking was severe enough to collapse many cliffs, trigger landslides, and topple stone buildings and chimneys, and as aftershocks persisted many residents slept uneasily for days to come. Several residents began to self-evacuate from Kaʻū due to damage and near-constant shaking, later counting themselves lucky if this was the worst of their experience.

The continued migration of magma from Maunaloa’s summit down into the Southwest Rift finally released its southeast flank in unrivaled fashion through the largest earthquake ever reported in Hawaiʻi around 4pm on April 2, 1868, estimated at magnitude 7.9 based on the geographic distribution and intensity of reports. It triggered further widespread collapses of cliffs, dwellings, churches and other structures beyond Hilo, causing perhaps 22 fatalities (reports are somewhat ambiguous). It initiated a combination landslide and mudflow at Keaīwa, near today’s Wood Valley, which consumed 31 people, 10 houses and many livestock. Finally, it also immediately triggered a sequence of tsunami waves which swept onto the island’s southern shore, killing perhaps 47 people and taking 108 houses. In its wake, the whole southern coastline of Hawaiʻi Island from Kaʻu to Kapoho had subsided significantly in many areas, changing the nearshore landscape by sinking beaches and points and flooding inland features and groves.

Cross-section of the southern flank of Maunaloa , showing the hypocenter of the 1868 Great Kaʻū Earthquake at the base of the volcano where it sits atop the old ocean floor, and map of Hawaiʻi Island showing the maximum extent of fault slip during the record event (via USGS-HVO Volcano Watch on March 29, 2018).

Already damaged by the magnitude 7.1 on March 28, the Wai‘ōhinu church collapsed during the magnitude 7.9 great Ka‘ū earthquake five days later in 1868. Photo by Henry L. Chase, published in "Volcanoes of Kīlauea and Mauna Loa on the Island of Hawai‘i" by W.T. Brigham, Bishop Museum Press, 1909; via USGS-HVO Volcano Watch on March 29, 2018.

The mudflow was one of the stranger effects triggered by the earthquake in Kaʻū, as it started a landslide which then released groundwater impounded within the hillside. The red mud at the front of this cold flow moved 3 miles in less than 3 minutes, 6 feet deep and hardened after several days when the flow of water issuing from the hillside decreased and eventually ceased. Many farmers perished, though as with a later stage of the disaster there are miracle stories of survival, in this case from occupied houses spared but surrounded by the mud.

Although records of events on Kīlauea during this time are sparse and sometimes ambiguous, we can reconstruct a potential sequence of events informed by recent science and observations. The initial effects on Kīlauea likely date back to the earlier 7.1 quake, with collapse along the southwest rim. Following the Great Earthquake on April 2, further widespread cliff collapses were reported, and a short eruption occurred on the floor of Kīlauea Iki from the pressure on cooling magma underground.

Kīlauea as painted by Tavernier after a large earthquake affected lava lakes at the summit in 1885, perhaps a similar view to the draining lava in 1868. Image from USGS Open-File Report 2018-1027.

“The Kīlauea Iki 1868 lava falls off the coherent temporal trend for Kīlauea lavas. This evolved lava may have been related to early 19th century magma as shown by arrow.” Figure 12 from Garcia, M.O., Pietruszka, A.J., & Rhodes, J.M. (2003). A Petrologic Perspective of Kīlauea Volcano's Summit Magma Reservoir. Journal of Petrology, 44, 2313-2339.

Modern chemical analysis by Garcia, Pietruszka, and Rhodes (2003) suggests the source magma for the Kīlauea Iki eruption had evolved for several decades, perhaps from the 1832 eruption 36 years prior, rather than being fed by fresher, hotter magma. Within the main active lava lakes at Halemaʻumaʻu, the nature of the eruption began to change as lava subsided and reduced in area, progressing over the next 5 days, at which point lava was no longer visible on Kīlauea.

Map view of the extent of the 1868 flow shown in yellow on the floor of Kīlauea Iki crater. Figure 2b from Orr, T. R., Hazlett, R., DeSmither, L., Kauahikaua, J., & Gaddis, B. (2021). Correcting the historical record for Kīlauea Volcano's 1832, 1868, and 1877 summit eruptions. Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research, 410, 107168.

Over this time, the lava was draining somewhere, likely into one of Kīlauea’s rift zones widened by the 7.9 event. Numerous smaller earthquakes would have tracked the migration of magma within the volcano, as we have seen in a recent eruption in 2018 on the East Rift and in a recent intrusion in 2023-24 on the Southwest Rift. In 1868, a vague report of “eastern craters opening and smoke in the direction of Puna”, as put by USGS Professional Paper 1806, suggests the possibility of an East Rift intrusion somewhere during this time. Complicating matters, a fire was also separately reported in Puna during this time, perhaps but not noted to be related to the earthquake.

However, as Kīlauea’s Southwest Rift actually did erupt at an unknown time within the next few days, it seems a likely candidate for the intrusion responsible for summit draining. Perhaps the intrusion led to what came two days later, when another earthquake around magnitude 7 further opened the Southwest Rift. While we interpret those two events into the next phase of the sequence, a conclusive determination is difficult because later reports of damage and subsidence integrate both those events and the earlier magnitude 7.9.

Annotated photo of Kīlauea Iki circa 1901, showing the extent of the 1868 flow on the floor of Kīlauea Iki crater. Restored with Capcut AI from Figure 9a of Orr, T. R., Hazlett, R., DeSmither, L., Kauahikaua, J., & Gaddis, B. (2021). Correcting the historical record for Kīlauea Volcano's 1832, 1868, and 1877 summit eruptions. Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research, 410, 107168.

Clip of the Pacific Commercial Advertiser from April 11, 1868, which reports the existence of a third earthquake larger than magnitude 7 during the 16-day sequence of events.

Following the April 2 earthquake, the Pacific Commercial Advertiser reports “another of nearly equal force at 12:30 on the morning of the 4th”. This is corroborated by USGS Professional Paper 1806 which provides that “the 1868 earthquake aftershock sequence included a second earthquake of high magnitude (~M7) beneath Kīlauea’s south flank, resulting in the generation of a second tsunami.” This becomes the third earthquake greater than magnitude 7 within the 16-day sequence.

How could a magnitude 7 earthquake be “forgotten”? Perhaps it was because it released much less energy than locals had just experienced in the magnitude 7.9 two days earlier. Newspapers of the era were only published weekly with information often exchanged by written letters, so maybe reports of the two earthquakes were confused. When damage was assessed after April 4, it may not have been possible to separate the effects of the 7.9 from the 7.0 in areas without eyewitness accounts. USGS PP 1806 notes “it appears that Kīlauea had more damage than one would expect” before accounting for the additional earthquake. In any case, much of the scientific literature does not mention this third big quake.

Map of Kīlauea’s 1868 eruptions drawn in yellow, at the summit within Kīlauea Iki at the top right, and 9 miles down Kīlauea’s Southwest Rift at the bottom left. USGS data plotted on Google Earth.

Close-up map of Kīlauea’s 1868 Southwest Rift eruption, with new lava outlined in yellow. Such a small footprint suggests the eruption was only briefly active, perhaps for only a few hours. USGS data plotted on Google Earth.

As a result, there is ambiguity in the timing of Kīlauea’s events, but one believable scenario is that Kīlauea Iki erupted on April 2 as a result of the impact of the 7.9, and that perhaps the initial draining into the Southwest Rift began shortly thereafter. Magma pressurizing Kīlauea’s Southwest Rift may have triggered the April 4 earthquake, further opening the rift and causing significant collapse at the summit, while feeding a small and brief eruption 9 miles away. It’s also possible that Kīlauea Iki erupted on April 4, in conjunction with the magnitude 7 event.

Could the 7.9 still be solely responsible for all these effects? Perhaps, although as explained by a 1994 USGS Volcano Watch article, “extension across Kīlauea’s southwest rift zone would not be expected [from the interpreted slip area during the magnitude 7.9 earthquake]… because the southwest rift zone was not a boundary of the proposed active block”. Thus this third large earthquake would have been the perfect candidate to cause that opening and extension.

It does seem that from April 2, Kīlauea’s lava lakes began to shrink and drain as a result of the 7.9, and that by April 5 there was no lava visible on the volcano. The April 4 quake may have accelerated the process and enabled a bigger summit collapse, which occurred to a depth of 300 feet with a volume nearly one-fourth of the collapse in 2018. As that recent experience taught us, many earthquakes would accompany such a collapse, and shaking was widely felt as far as Hilo until April 9, when finally people there reported getting a restful night’s sleep as the collapse had presumably ended.

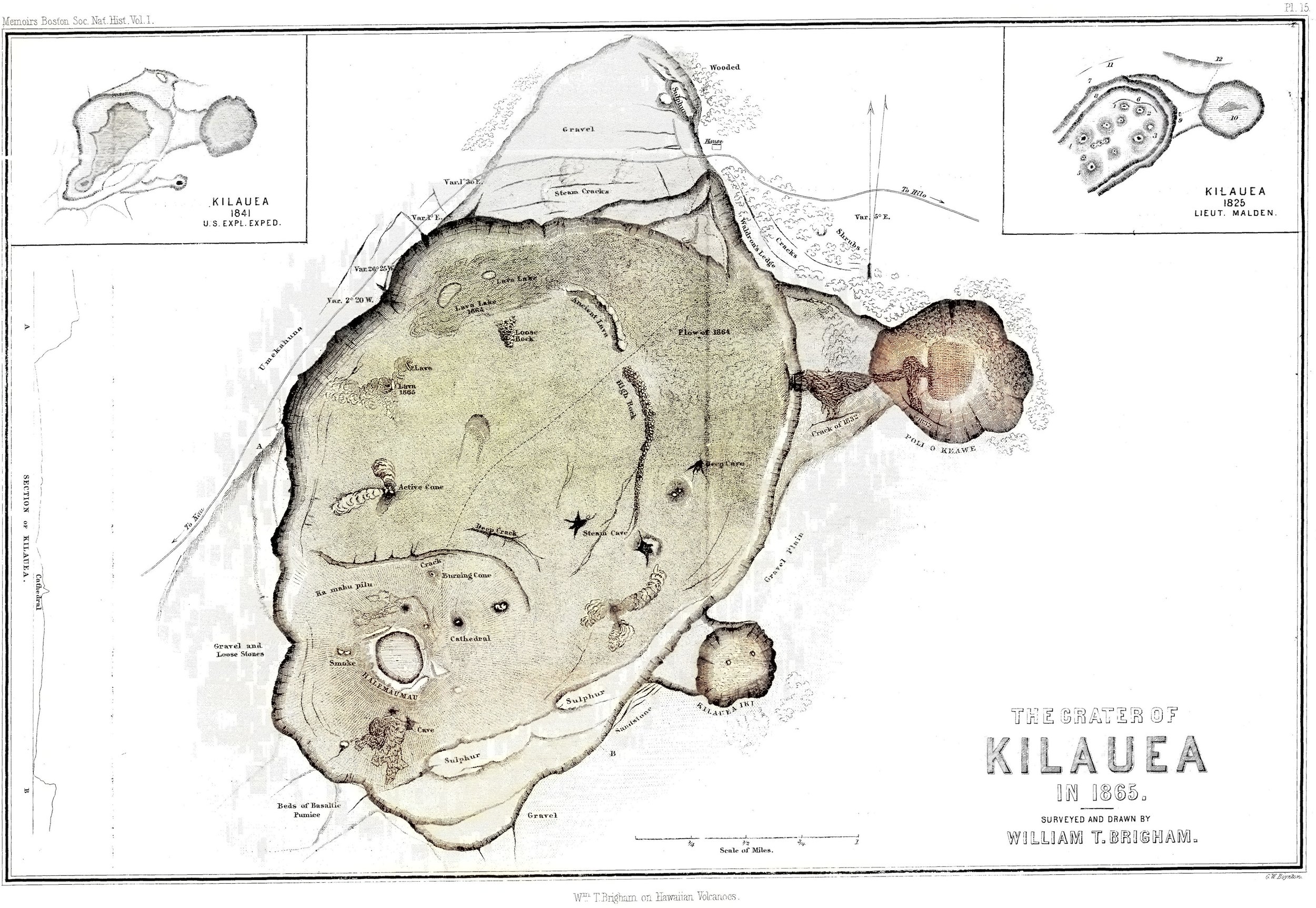

Map of Kīlauea caldera in 1865, prior to the 1868 collapse, colorized with Capcut AI from historic paper map entitled: Wm. T. Brigham on Hawaiian volcanoes (1868), G.W. Boynton, sc. Pl. 15 : Crater of Kilauea in 1865, surveyed and drawn by William T. Brigham. Memoirs Boston Society of Natural History, vol.1.

Map and cross section showing the collapsed area within Kīlauea caldera following the events of 1868. Colorized with Capcut AI and enhanced with 1865 map (see below) from Brigham, W. T. (1909). The volcanoes of Kilauea and Mauna Loa: B. P. Bishop Mus. Mem., vol. 2, no. 4, 222 pp., Honolulu.

As challenging as 2018 was for residents to experience, we can only imagine how much more demanding the combined events of 1868 would be. Beyond Kīlauea, the intrusion in Maunaloa’s Southwest Rift which began the cascade of phases had still been migrating south, and was due to erupt massively in Kahuku on April 7.

Kaʻū had been quieter for several days following the Great Quake and its immediate aftershocks, but on April 6 the shaking intensified again. Many people slept outside that night, fearful of houses damaged by countless earthquakes coming down upon them. Fine ash is reported to have fallen overnight, well before the eruption of any lava.

Maps of Maunaloa’s summit before and after the events of 1868, showing an enlarged crater presumably due to collapse during the sequence. Four years following the collapse, lava returned to Maunaloa summit and began filling its deepest craters, such that the 1874 shows a flat crater floor at its center. Kīlauea has recently undergone a similar transformation, where six years following its summit collapse, its inner crater has been largely refilled to a flat crater floor within an enlarged area of subsidence. Maps by Thomas Jaggar from The Volcano Letter, Nov. 19, 1931.

USGS map of the 1868 lava flow along with other historic lava flows from Maunaloa in the southern part of Hawaiʻi Island. From USGS Volcano Watch article, May 19, 2022.

It seems likely that Maunaloa’s summit began to collapse at some point following the Great Quake, intensifying on April 6 with renewed seismicity. As we experienced on Kīlauea in 2018, the collapses and accompanying quakes probably lasted until the end of the coming eruption, which was to be April 11. According to preliminary work by the USGS Hawaiian Volcano Observatory, despite that relatively short time, the collapse of Maunaloa in 1868 may have been larger than that of Kīlauea in 2018 which took a full 3 months to complete. Maps from before and after the collapse illustrate the enlargement of Maunaloa’s caldera, Mokuʻāweoweo, though the innermost collapse craters were refilled by subsequent eruptions (also similar to Kīlauea since 2018).

Finally, Maunaloa’s magma would re-emerge at Kahuku on April 7, 1868, 11 days after first triggering the cascade of events. The eruption began around the 3,000-foot elevation, more than 10,500 feet below Maunaloa summit, fed by magma moving into the Southwest Rift from beneath the summit above. Fissures emerged upslope of the residence of Captain Brown, near where a crater 60 feet wide issuing steam and sulfurous gases had formed earlier in the sequence. Lava quickly overran the farm and what remained of its structures damaged by the earthquakes. The fissure line would grow to over two miles long, with four distinct lava fountains over 500 feet high established over the coming days. Lightning and thunder accompanied the eruption, and vog was widespread with the whole island “shrouded in darkness” according to the Pacific Commercial Advertiser. The massive volume of gas emitted was noted to be larger than that produced throughout the much longer 1859 eruption, still fresh on people’s minds.

Part of the 1868 flow at Kahuku, where lava cascaded down a steep slope. Photo by H. L. Chase from the Mission Houses Museum Archive via Wikimedia Commons, restored with Capcut AI.

The eruption spawned lava flows that split into several branches, some flowing southeast and some southwest. The largest became a huge river of lava which reached the ocean 10 miles away in only three and a half hours, generating furious ocean entries with explosions that formed a littoral cone. Several close calls and miracle escapes were had, but ultimately there were no human casualties unlike the week before. The eruption lasted 5 days, allowing a few off-island visitors just enough time to travel to Kaʻū to witness flowing lava. Their accounts make this phase the best documented of the whole sequence, after which the destruction included 37 houses and over 100 livestock while covering over 1.5 miles of public roads. Following the eruption, steaming cracks were noted to continue upslope from the fissures to a distance of 10 miles, but finally the worst of the earthquakes were over, and Kaʻū residents could finally rest and begin to recover.

Aerial photo of the lower part of the 1868 eruption, where its dark lava flows meet the sea south-southwest of their source. Maunaloa’s upper reaches are at the top left of the image, while Kalae (the island’s “South Point”) is just off the image to the right. USGS photo taken in 1954, from the USGS Volcano Watch article on April 5, 2018, colorized with Capcut AI.

The record-setting 7.9 earthquake by itself would cause significant damage Statewide were it to happen today. Local quakes don’t give much time for tsunami warnings to be issued, arriving on shore within minutes and also affecting the entire State. Both of these potential events rely on education and preparedness to minimize their impact, especially close to the epicenter where effects are greatest. Emergency responders would be challenged by the occurrence of a second disaster while responding to the first, then by a third and fourth disaster in turn (M7.1, M7.9 & tsunami, M7, Maunaloa SW Rift eruption), with extreme damage locally and other impacts Statewide.

For earthquakes, residents can secure their space, make emergency plans, organize emergency supplies and minimize financial hardship, according to the Earthquake Country Alliance.

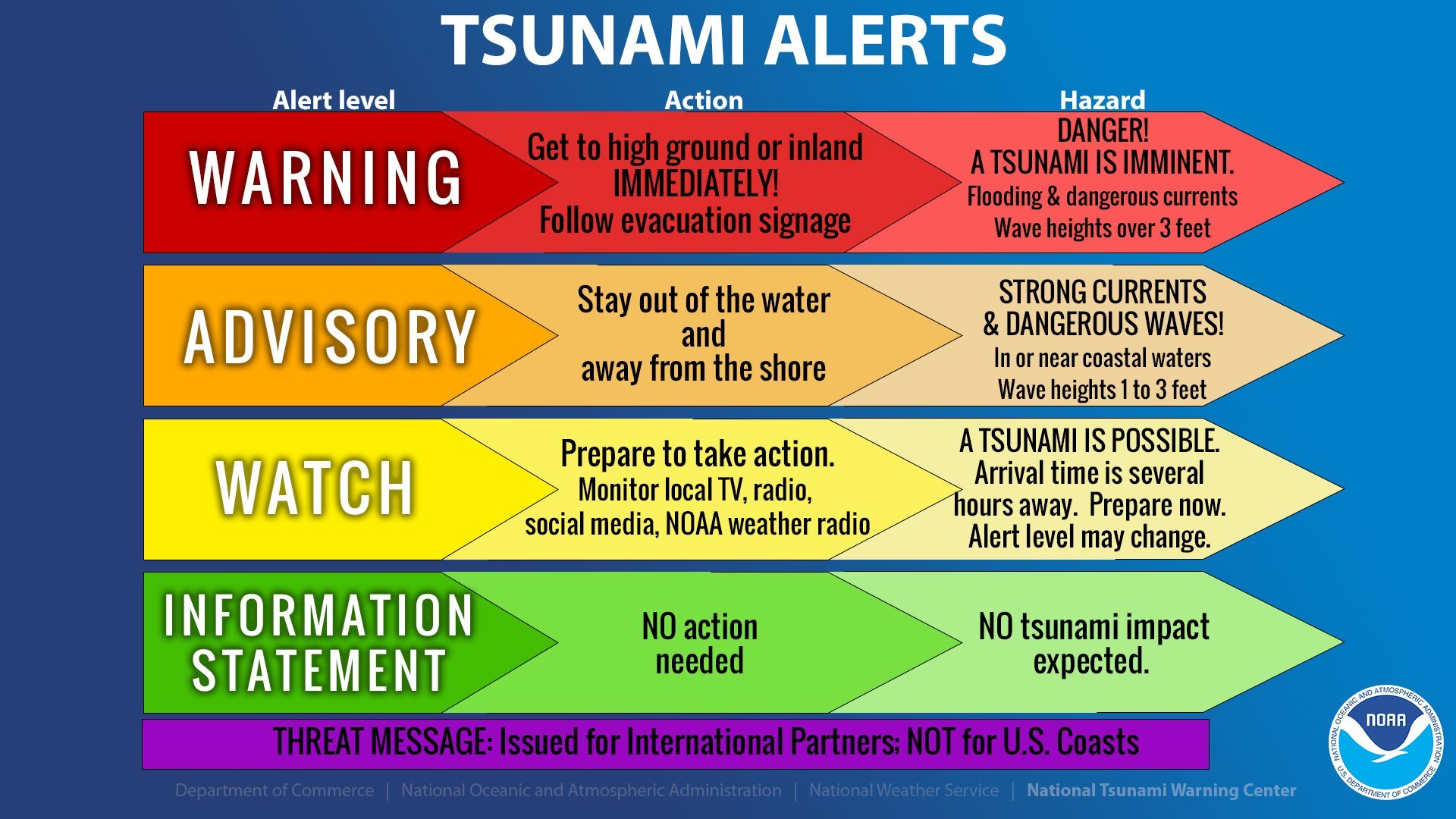

Natural and official tsunami warnings, from NOAA’s tsunami.gov.

For local tsunami, anyone at the beach who feels an earthquake strong enough to make standing difficult, or sees the ocean recede significantly such that the reef is exposed, or hears a loud roar from the ocean, should immediately evacuate inland and uphill without waiting for any sirens or other prompting, helping and alerting others nearby. Planning a gathering point inland of the beach can help people reconnect, with everyone taking urgent action once tsunami warning signs appear. Precautions can be taken beneath cliffs and steep terrain especially during seismically active periods, with the expectation of possible rockfalls and landslides.

Tsunami alert levels from NOAA’s National Tsunami Warning Center.

Beyond personal preparedness, HVERI is working with communities alongside Hawaiʻi County Civil Defense, Vibrant Hawaiʻi and the network of island-wide Resilience Hubs to improve the resilience of our systems and our ability to respond to such a series of disasters. The events of 1868 would serve as the ultimate test for preparedness, and while we hope it will be a long time before we see a similar sequence, we cannot be ready soon enough. To this end, let us know if you'd like to join us or the Resilience Network through volunteering, or if you’d like to support us financially in this important work, as our mission is to improve disaster preparedness, response and recovery through volcano education and resilience network building.

Ready to take action? Dive into preparedness for earthquakes and tsunamis by following these links:

Seven Steps to Earthquake Safety from the Earthquake Country Alliance - https://www.earthquakecountry.org/sevensteps/

Four Key Aspects of Tsunami Preparedness from Wai Hālana, State of Hawaiʻi -

https://waihalana.hawaii.gov/2021/04/12/tsunami-awareness-month-hawaii/

Note: We use a preferred traditional spelling of the volcano by the local community as “Maunaloa”, though it has not yet been formally adopted by either the State or Federal Board of Geographic Names who still officially refer to it as “Mauna Loa”. This follows in the same spirit as the spelling of “Maunakea” gaining broader acceptance.